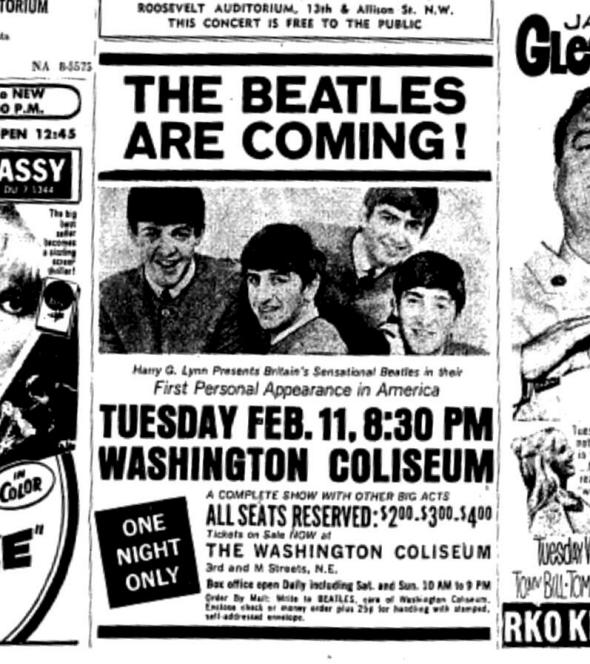

Adjusting for inflation, those tickets ranged in price from $15 to $30. These days $30 will get you in to see St. Vincent at the 9:30 Club but prices to see Kings of Leon at the Verizon Center start at about $60.

There are a number of concomitant reasons why, despite it being the hottest show in the world, it was so much cheaper than any popular concert would be in 2014.

First is the simplest of supply/demand arguments: The population of the U.S. in 1964 was an estimated 191,888,791, compared to 317,511,425 right now. Sure, the local population of D.C. at the time was somewhere between an estimated 756,510-763,956, which is probably around 100,000 more than today, but this wasn’t the first Beatles show in D.C., it was the first show in the United States.

Second, to continue on the demand side: Culturally, in 1964 rock concerts were just not universally acceptable events to attend, especially for young people, therefore the base of potential demand was significantly lower than it would be in 2014. Today, almost nobody bats an eye at the prospect of seeing a concert. Massive arenas can’t contain the demand for teen-focused acts, because nearly every teen is capable and wants to see rock concerts. Almost any parent would have little problem letting their teenagers go to the local arena/venue/high school gymnasium to see live rock and roll music. It’s not the devil’s music anymore, causing teenagers to worship Satan, do drugs, have sex and drop out of school. Rock and roll is so mainstream those thoughts are just laughable.

Additionally, in 2014, there’s several generations of folks older (and much richer) who make up part of the demand for rock concerts. In 1964, that was almost not the case at all, as 1964 was seeing the first ever generation of popular rock music acts. Sure, some less-than-upstanding parents of kids in 1964 would have been amenable to rock and roll music, or were probably familiar and fans of its antecedents, but that was nowhere even hear the norm. Now, go to see any concert, and I guarantee there will be plenty of 30- and 40-year-olds standing in the back, folks who were easily capable of paying the $60 ticket price for Kings of Leon.

Meanwhile, on the supply side: The ideal arena/venue size to see a concert has not grown with demand and population growth. Sure, we have outdoor venues that hold lots more people, and the Verizon center is probably bigger (but not much) than the Washington Colosseum. But, once you get much larger than that, the magic of the show diminishes, so venues are not build to hold the capacity that would match the 1964 population. This creates supply shortages, which creates higher prices. Of course, when prices are controlled, scalping becomes a more popular consequence, driving prices even further.

The economics of musical acts in 2014: On New Years Eve 2014, Billy Joel, a fairly popular musician, but hardly Beatles-in-1964, played a packed house at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. The arena packs in about 18,000, about double the capacity of the Washington Coliseum. Tickets were about $64.50-$199.50.

The good news is that supply has, in another way, exploded. There are far more venues, and lots and lots more bands out there than ever before. Small venues, large arenas, and everything in between. Granted, there’s only so much cultural bandwidth for super-stars with super-high-demand tickets, but there are plenty of real bargains near the bottom—great bands that might cost you $5-10 to see on any given night.